Mozambique was regarded as an African economic success story until relatively recently. Although still one of the poorest countries in the world, annual growth has averaged 7% over the past decade. Huge coal and gas discoveries held the prospect of more rapid growth in the future. Yet the government is now struggling to regain its reputation for sound economic management, which was badly shaken by revelations over hidden debts in 2016.

Three state owned companies, Empresa Moçambicana de Atum (Ematum), ProIndicus and Mozambique Asset Management, were found to have taken out more than US$2 billion in loans from Credit Suisse, BNP Paribas and VTB of Russia. All three parastatals are owned by the national intelligence agency. Ematum received US$850 million to finance the purchase of tuna fishing boats and the other two used US$1.2 billion to buy patrol boats and set up a radar surveillance network. The loans have had a big impact on the economy, as they:

• were taken out in secret but guaranteed by the government beyond levels agreed under the constitution.

• pushed the national debt as a percentage of GDP beyond 100%.

• raised big questions over governance, including what exactly the national intelligence agency was doing investing in tuna fishing.

• generated fears over corruption, as the sums paid seem to have been excessive and some of the money has disappeared.

Joseph Hanlon, who has written on Mozambique for many years and who is a senior research fellow at the UK’s Open University, says of the three contracts: “Nobody who did serious due diligence would have said it was reasonable. Nobody.”

“Nobody who did serious due diligence would have said it was reasonable. Nobody.”

Despite this, Maputo has failed to bring those responsible to account. The scandal had an immediate, direct impact. All 14 national and multilateral organisations that provided about 25% of the state budget, led by the IMF and including the UK, US and Swedish governments, suspended financing. They continue to fund education, health and other projects directly but look unlikely to resume budgetary support until the apparently illicit loans are accounted for.

The debt crisis resulted in the government defaulting on its repayments on $727 million in Eurobonds last year. US corporate investigation firm Kroll Associates was appointed to carry out an audit but was unable to find out where $500 million of the Ematum loan had ended up. However, it discovered that all three firms had overpaid on their acquisitions and, according to the attorney-general’s office, uncovered “a number of facts substantiating financial offences”, indicating “possible criminal offences”.

At the end of January, the state prosecutor launched legal proceedings against executives in the three companies. In addition, the administrative tribunal is now seeking to establish responsibility for the borrowing. It has the power to impose fines but not seek criminal prosecution, so it may not be sufficient to placate donors. The US Justice Department and the FBI have launched their own investigations.

During the course of 2017, the Bank of Mozambique was forced to intervene with a succession of interest rate rises aimed at stabilising the economy. The national currency, the metical, recovered some of the ground it lost when the scandal broke, although higher interest rates also depressed growth. The IMF estimates growth of 3.1% for 2017 and forecasts 3.2%for this year and 3.4% next year. This more modest growth partly stems from the debt crisis but is also the result of a lull in economic activity before much greater coal and later gas exports kick in.

According to government figures, 87% of Maputo’s sovereign debt is owed to other governments or multilaterals, with 13% taken out as commercial loans. Yet the latter place a huge strain on government finances as they account for 50% of debt servicing costs. Maputo is to present its debt restructuring proposals to creditors at a meeting in London on 20 March.

Even if agreement is reached, the scandal has already had a big indirect impact on international perceptions of the country. Perhaps the best way of measuring the damage done is Transparency International’s annual Corruptions Perception Index, which awards national economies scores out of 100: those considered absolutely clean are given 100 and those totally corrupt 0.

Mozambique’s rating fell from 31 in 2015, before the loans were revealed, to 25 in 2017.

It is now rated as 153th “cleanest” out of the 180 countries included but it is worth noting that, at 31, the country hardly had a positive rating even before the debts were revealed. Frelimo has ruled the country since independence but the international community had not previously regarded the party’s dominance as a threat to standards of governance. That has now probably changed.

The case has boosted concern over rising levels of African sovereign debt. The anti-debt campaigns of the 1990s and into the new millennium resulted in widespread debt cancellation, giving many African governments a fresh start. Many have subsequently taken on new debt, often for infrastructural projects that they hope will raise their long-term growth prospects. It remains to be seen whether they can cope with this new debt. The median level of sovereign debt in Sub-Saharan Africa rose from 34% in 2013 to 48% last year. Mozambique’s Economy and Finance Minister, Adriano Maleiane, says that Maputo wants to return its public debt to “sustainable levels”.

Coal investment insulated

The debt scandal will probably have relatively little impact on the sectors expected to generate most growth over the next few years. Over the coming decade, Mozambique is expected to become a coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporter of global importance thanks to tens of billions of dollars in investment. As both industries will be export-orientated, their development hangs mostly on the direction of international prices and, in the case of coal, on the construction of export-orientated rail and port infrastructure. Poor financial oversight by the government or frailty in its finances will have little direct impact.

Maputo hopes that coal projects in the Moatize Basin in the northwest of the country will yield more than 100 million tons/year in coal exports, plus feedstock for power plants and other industrial consumers within the country. Brazilian mining giant Vale is already committed to producing 22 million tons/year and with Japanese partner Mitsui has financed the construction of a new railway to Nacala, the deepest natural harbour on the east coast of Africa. Mozambique has both thermal and coking coal reserves and so its coal prospects are not solely tied up with power generation.

The hit to government finances inflicted by the debt scandal could affect the ability of state owned Portos e Caminhos de Ferro de Moçambique (CFM) to provide its share of investment capital on coal sector transport projects. However, private sector investors, including Vale, Mitsui, Italian Thai Development and India’s Essar Ports, are providing the lion’s share of the required investment in developing four railways to connect the coal mines with export terminals at the Indian Ocean ports of Beira, Nacala and Macuse. CFM has only become a minor equity investor in some projects at the government’s insistence. Maputo could drop this requirement if required, allowing CFM to concentrate on its role as sector regulator.

Gas boom delayed

As with coal, the development of planned LNG schemes depends almost entirely on anticipated international demand for gas. The main threat to Mozambican gas exports is the string of other LNG projects under development elsewhere in the world, particularly in Australia and the United States. LNG developers invariably need to have most of their production capacity tied up in very long-term contracts, often of 20 years, in order to justify construction.

Fears over surplus global production capacity have already delayed the development of the planned onshore LNG plant, which would be supplied with gas by both of the main consortia operating offshore, led by Anadarko and Eni respectively.

First gas is now not expected from the project until 2024 at the very earliest. Concerns over global warming are likely to come to Mozambique’s rescue. Many countries, including China, are seeking to reduce their dependence on coal-fired power generation for baseload capacity, using more gas in its place.

However, Mozambique should export its first LNG before then, in 2022, as Eni is pushing ahead with its US$8 billion Coral South floating LNG (FLNG) project. The Italian company is keen to develop Eastern Africa’s first FLNG project, in part in order to test the technology. With gas reserves of 180 trillion cu ft in and around the Rovuma Basin, this project should just be the first of many.

Outlook

Providing international prices underpin development, the gas and coal sectors should enable a step increase in Mozambican GDP. However, GDP is not the only measure of successful economic development. The oil, gas and mining industries generate relatively little employment per unit of GDP. Much smaller projects in other sectors, including in agriculture and independent tourism, have the potential to generate many more jobs.

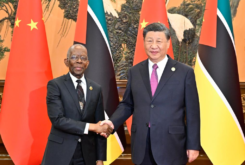

Sound governance and economic stability are vital if the small and medium sized enterprises operating in such sectors are to prosper. It is therefore vital that Maputo provides full disclosure on the debt scandal and puts measures in place to ensure there is no repeat performance. President Filipe Nyusi has pledged to adopt a zero-tolerance policy on corruption but must now deliver on that promise.